U-turning

What you don’t know.

We make choices, we re-think them. Who hasn’t wanted a way out of a bad choice? It can seem there’s no way. Making a u-turn requires moving what seems immovable, rethinking assumptions, finding a way.

My new novel (available for digital pre-order at an excellent price!), What You Don’t Know, is about how people turn completely around in their lives. Chloe makes choices she regrets but can’t imagine a way out—too much upheaval required, too many people’s lives in the mix. Until she does. And again, she does.

There’s also an interfering ghost.

Poet Mary Ruefle has said every poem is about change. And every novel? Change is the story of everything.

If you’re over 30 it’s likely the world you knew when you were young isn’t there any more. It’s been torn down, paved over, rezoned, remodeled, sold or altered in unimagined ways. One of my characters returns to a childhood home in the Blue Ridge, for example, to find a three-story mega mansion in its place, all glass and stone.

My first u-turn was in college. I majored in psychology, but not the clinical kind. My department focused on behaviorist research; clinical psych was scorned as soft science. I assisted the rat professor, a kind, funny man with a nose that shaped his face like a rat’s. He often came to class with a furry white creature on his shoulder. The rats liked him. They didn’t know what he planned to do to them.

As lab assistant I learned to anesthetize them, shave their scalps, drill a hole in the skull and insert an electrode. It terrified me. I was sure I was torturing them. After surgery the poor rat pushed a lever to get some reward. I have no idea why this research mattered, if it did. I began to over-anesthetize those who wriggled when I drilled (most did, probably reflexive). Reader, I killed them. Mercy killing I thought, though it was accidental. My professor took me off the project, but not before he offered me a cocktail of orange juice with the ethyl alcohol we used as anesthesia.

Spring break, senior year, I went to New York with a friend and interviewed at the Rockefeller Institute as assistant to the behaviorist who wrote the books we used. I was excited about living there, young and free. I wanted the big pond and ignored the obvious difficulty with the job. Returning to North Carolina I told my professor I was hired by his mentor, and he gently reminded me: you hate animal experimentation. Then added: you’ll probably just get married anyway. Really, he said that.

Offended, I left his office, knowing he was both right and wrong.

I was also taking literature courses and was offered a fellowship I hadn’t applied for. Yes! My brain (and parents) asked what I hoped to do with an MA in Lit, I’d invested so much in psych, and how could I give up such a good job? But all the irrational parts of myself (heart and gut) leapt at the offer.

I escaped the job at Rockefeller, a fate I could not have endured. Experiments on monkeys? Not a chance. Instead I got Emily Dickinson, Victorian literature, Wallace Stevens, T. S. Eliot. I wrote my thesis on “Burnt Norton.” I’ve never stopped reading it.

I taught lit a few years but eventually made another u-turn, returning to psychology, the clinical kind, to become a therapist. Better to heal than hurt.

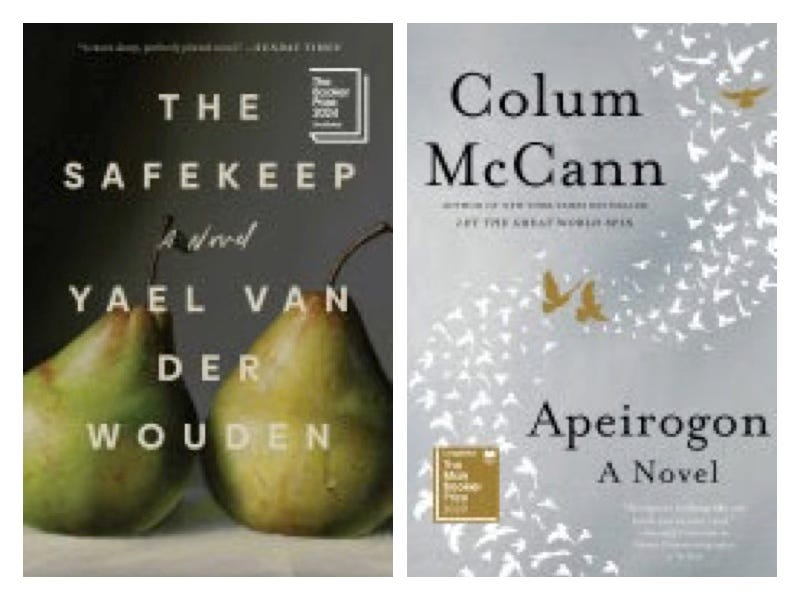

Change drives fiction. Two books based on the aftermath of the Holocaust send characters on serious u-turns. Colum McCann’s Apeirogon, long-listed for the Booker, re-creates a true story about Bassam, a Palestinian, and Rami, an Israeli. Bassam’s 10-year-old daughter was killed outside her school by an Israeli soldier. Rami’s 13-year-old daughter was killed by a Palestinian suicide bomber. They become unlikely friends; they work together for peace.

Bassam, imprisoned, beaten regularly by Israeli guards, has a revelation: I began to think…about the Jews too. And I knew now this Holocaust was real…And I began to think, reluctantly first, that so much of the Israeli mind must have stemmed from that, and then I decided to try to understand who these people really were, how they suffered, and why it was that in ’48 they had turned their oppression back on us again and again, stole our houses, took away our land, gave us our Nakba, our catastrophe. We, the Palestinians, became the victims of the victims. I wanted to understand more.

Rami, the Israeli, tries to ignore the conflict until his daughter is killed. He finds his way to a bereaved parents’ group where he encounters the realities of the Occupation, and his mind opens. The force of their mutual grief turns Bassam and Rami toward each other.

In The Safekeep, short-listed for the Booker, a Dutch woman is cornered after the war into sharing her home with a Jewish woman she intensely dislikes until a series of events change her. She falls in love with this woman. Letting her into her bed, the terror was as wide as the want: a boulder moved from the gaping mouth of a cave. Her world reels, like walking on the frozen canal: a miracle, she thought, to stand so solidly on what could also engulf you.

U-turns are transformations, epiphanies. We make them because we don’t know things until we know them. We look both backward and forward. More experienced, and sometimes more hopeful, we head towards something new, not just away from something.

Desperately now, we await signs of understanding, empathy, revelation, a community of feeling, a miracle, something to propel our country toward a U-turn.

Is there a hot link to order your book???

The u-turns in my life whether foisted on me from outside forces or self imposed have given me a life beyond my wildest dreams. So grateful for the opportunity and willingness to change.